Dueños del agua

The dispossessed

Dozens of indigenous communities in the southern Andean region of Peru watch the wealth from mineral mining pass by their homes without electricity or water. The stories of the inhabitants of the upper regions of Apurimac and Cusco include comuneros in conflict, water exploitation rights issued without proper surveys, inefficiency in public spending, loss of communal property, and violation of rights to prior consultation.

August 28, 2018

W ho are you coming with? asks Rogers Ccoropuna, President of the Chuicuni community.

The icy wind mocks the sun in the heights of Apurimac at 3,800 meters above sea level. It is harvest time in the Andes and the wheat fields shine brighter than ever on the farm of the Chuicuni’s leader, located in an indigenous Apurimeña community located beside one of the largest and richest mining projects in Peru: Las Bambas, operated by the Chinese transnational MMG Limited. The midday sun reveals the harsh features of the Quechua leader. He approaches slowly and hesitantly, and calms his barking dog. He greets us. His hands are cold.

- Who are you coming with? he insists.

- It is only us.

- I don’t believe you. Most of the journalists come here on behalf of the mine.

Mistrust has become the rule of coexistence in Chuicuni. The influence of Las Bambas extends across all the communities located in the district of Chalhuahuacho, the most important town in size and commerce in the area. The mine sponsors the radio stations and their programs. In restaurants the diners are mineworkers; in hotels the guests are consultants, engineers, or other company employees. It is the same in the bars, the discotecs, and the nightclubs that operate every week.

Chuicuni is located next to the mining project and is 10 minutes from Chalhuahuacho. But it has no electricity, no stores, and no houses of more than one story. The people capture their water from a spring and it flows untreated through a pipe to a tank in the center of town.

- Each comunero has contributed between 10 and 15 soles to cover the cost of this work. We did it on our own. Not the municipality. Not the government. Just us.

The people of Chuicuni have built everything by themselves. The only way to get here is across a pedestrian bridge over a river. They built it “without technical approval,” the president of the community points out with some annoyance. “We do not really know how many people or how much weight it can bear.” But today the main concern of Rogers Ccoropuna is not the bridge, but the water: What will happen if the spring that supplies the entire town dries up one day? What if the mining project affects the quality of water?

“Journalists are always coming. But they are never going to report what is happening. And nor are you.” says Rogers Ccoropuna.

The strip that joins Chalhuahuacho (Apurimac) and Espinar (Cusco) is known as the southern mining corridor due to the number of mining megaprojects that are concentrated here: Las Bambas (of China MMG Limited), Antapaccay (of Glencore, based in Switzerland ) and Anabi (of the Peruvian group Aruntani) are all located in this area. Peru is the world's second largest producer of copper, zinc, and silver. And it is estimated that 40% of the national copper production comes from this corridor.

The leader of Chuicuni is fearful of the future. He is afraid that the same thing will happen here as it did in other nearby mining areas—such as Espinar, in Cusco—where the communities have reported the loss of springs and impacts on water quality.

- We are sorry to be living in this community. There is no point living so close to a mine. Journalists come, but they never report what is happening. Even you won’t.

CHUICUNI

[Watching wealth from a house without water ]

Life in Chuicuni starts before five in the morning at a temperature of four degrees. Above, from one of the highest hills behind the community one can see, to the right, the trucks and tippers of the mining operation. On the other side there is an enormous metal fence swallowing up the mountains: the mesh divides communal land from the private property of the company. The echo from the trucks breaks the silence of the mountains. Down in the village, the women get up to fetch water from the communal standpipe, and prepare breakfast for their children, whilst the men (some of them at least) take the cattle to graze.

Javier Huillca Puma is Vice President of Chuicuni. From the hilltop to which he has brought us—where the only resistance the wind encounters are the high-tension towers and where oxygen seems to disappear with each breath—he points out the boundaries of the community. “Our neighboring community was Fuerabamba, and our cattle went from one place to another without a problem. We understood each other. That doesn’t happen now,” he says.

In 2004 the government of Alejandro Toledo granted exploration rights to Las Bambas and with the start of operations in 2014 Fuerabamba was relocated to an urban area around Chalhuahuacho that had all the basic services. Chuicuni remained where it was, without water or electricity. And that was how it welcomed the giant new mining neighbor.

Since then, the comuneros coexist with noise, dust, and small tremors due to the explosions for mineral extraction. The 200 families of this community also saw how the mine installed a plant to treat the water that its workers use, and then how huge cables then plowed through the skies over their homes, taking electrical power to the mine, but leaving them in the dark.

The ANA granted 38 mining rights in Cotabambas over the last five years: 14 for groundwater and 17 for springs and streams.

Despite its proximity to the operations, Chuicuni is not considered within the mine’s area of direct influence. “The municipality tells us that we have to negotiate with the mine, and the company tells us that we must demand infrastructure from the municipality because we are within direct influence,” complains Rogers Ccoropuna.

The community president demands water and sanitation services. “We are afraid that the flow will change and we will run out of water. Sometimes only a small amount of water comes out and we have to queue up so there will be enough to go around,” he says.

The exploitation of Las Bambas began in 2014. There is not yet any evidence of its impact on water resources. Officials of the Local Water Authority acknowledged during a meeting with Ojo-Publico.com that there were no detailed water studies for the Apurímac basin when the water exploitation rights for mining were issued, and when the Environmental Impact Study was approved.

The most up-to-date studies—the same officials timidly clarified—were prepared by the mining company itself as part of the procedure to request the mining water use license.

A 2016 study Watershed Prioritization for Water Resource Management, established risk rankings of low, medium, high and very high-risk the use and disposal of water. Rogers Ccoropuna does not know it, but this document rates the Alto Apurímac Interbasin, where the land of his community is located, as very high risk. This conclusion is based on the analysis of several variables: quality, pollution, availability, droughts, population size, poverty rates, exploitation of aquifers, population and poverty rates, conflicts over water, and the demand for and supply of water.

In the province of Cotabambas alone—to which Chalhuahuacho and Chuicuni belong— the National Water Authority granted 38 rights for the exploitation of water for mining purposes over the last five years: 14 of these were for groundwater and the other 17 for springs and streams.

The inventories of the National Water Authority state that the demand for this resource as measured by the number of water licenses issued is 89% for agriculture, 9% for human consumption, 0.95% for industry, and 1% for the mining sector. However, enormous water consumption measured in millions of cubic meters hides critical situations and local realities like those for the populations in Cusco and Apurímac who have settled near basins where the mining megaprojects of the south are concentrated.

The inhabitants of one of the richest districts of Peru have no drinking water and their sewerage discharges into the river.

In Abancay, the capital of Apurímac department and eight hours from Chuicuni and Chalhuahuacho, a group of officials from the Local Water Authority (ALA), explain how water is managed in the basin. The technical team’s Carlos Moreno Huayhua and Reynaldo Pizarro Muñoz take part in the meeting. We are authorized only to take written notes to record the interview.

The ALAs are responsible for supervising the companies to ensure they comply with the authorized volume limits at the established points. However, the technical staff acknowledge that they are yet to perform this type of supervision because “the large mining projects approve them and the head offices review them.” That is, in Lima.

The officials claim that the problem in Apurímac is not access to water, but ownership of land. But, when we ask about the impacts of climate change over a longer period, the same officials argue that “the intensity and frequency of rainfall has changed” and that this increases the uncertainty about the future of water in highland communities, which, like Chuicuni, depend to a great extent on water for domestic use from springs and streams.

And it is precisely these water sources where is pressure is greatest.

In the four provinces of the southern mining corridor (Cotabambas and Antabamba, in Apurímac, Chumbivilcas and Espinar, in Cusco) alone, the government has granted 147 water exploitation rights for mining purposes. Of these, 40% are for extraction of groundwater, considered by experts to be a non-renewable resource.

The number of rights granted for agricultural and domestic purposes is much higher, but the collection points for mining are in areas considered to be headwaters, strategic locations for water generation that are regarded under current legislation as vulnerable.

Anemia and malnutrition are the principal health problems in the districts of the southern mining corridor.

The provision of rights to exploit clean waters for mining use has not gone hand in hand with the implementation of public works that guarantee access to safe water for urban and indigenous populations neighboring the mining operations. A review of budget execution by local and regional governments shows that more building construction and road maintenance has taken place than sanitation works.

Rogers Ccoropuna acknowledges that in the beginning his community was enthusiastic about the mining project: “We were totally in favor of the mining company, thinking that it would have a positive impact. They said there would be a school, basic sanitation, and electricity. So we supported it. But we have nothing.” Above the mud houses of Chuicuni, the huge cables line the sky and bring electrical power to the mine.

The day in Chuicuni ends when the sun goes down. At home, little 8-year-old Nadith—Rogers's niece—put a match to the candle to provide herself some light. She reads a book, Coquito, inherited from older cousins, with all its corners torn. The home is a kitchen-living-dining-bedroom. Outside, there are only shadows. We know they are people because they carry flashlights.

But they could be anything at all, like some of those haunted characters that the comuneros say appear at night to take the sheep away.

CHALLHUAHUACHO

[The contradictions of the wealthiest district]

One of the first things they tell you when you get to Chalhuahuacho is to notice the number of trucks circulating along its unpaved streets buried in puddles of water. The size of these 4x4s—all of them expensive brands and models—contrasts dramatically with the narrow and labyrinthine shape of the road they use. These powerful all-terrain vehicles were the first items that the farmers bought with the money for the sale of their land or the compensation they received from the Las Bambas mining project.

The richest district of the southern Andes with a population of 7,000 people, has one of the highest truck per person averages, yet has no potable water service and its waste is thrown into the river. Chalhuahuacho has 38 Quechua peasant communities and an estimated budget of 140 million soles this year. This amount is similar to that for each of the districts with the highest income in the country: San Isidro and Miraflores, in Lima. In only six years the budget for this municipality multiplied almost 30 times.

For the water to be safe, it must have 0.5 mg / L of chlorine, but in the samples analyzed the figure did not reach 0.1 mg / L

Chalhuahuacho seems to have been possessed by the same curse as other mining districts in Peru: millionaire budgets, poor execution of public works, stagnant social indicators and corruption. The current mayor Antolín Chipana Lima (of the Popular Movement Kallpa) is in prison and under investigation for money laundering and misappropriation of assets. Prior to his election in 2014, he was one of the most critical voices against mining. When he was detained in March of this year, police found twelve thousand soles in cash at his home. The investigation includes his then general secretary, Dionisio Maldonado, who was also arrested, and in whose house 50 thousand soles were found.

There is so much dust in Chalhuahuacho that cleaning the windows of cars, houses and shops is useless: a thick coat of dust covers everything, every day. To the 4X4 traffic are added cars, collective taxis, and, above all, the dozens of giant trucks that transport tons of processed copper every day.

There is another parade of vehicles inside the grounds of the Challhuahuacho Health Center. These are broken or damaged units. “They send us vehicles that are unsuitable for the area and they break down after a short time. And, in other cases they donate vehicles that already obsolete,” explained health personnel who preferred not to identify themselves.

The broken down vehicles are not the main problem for the health center. The biologist Hubert Firata says that anemia and poor water quality are threatening the health of the population of Chalhuahuacho and the dozens of indigenous communities located in the mine’s area of influence. “It is not safe. The water that reaches the houses comes through pipes, and only sometimes has the necessary dosis of chlorine added,” he says.

A week before our visit, Hubert Firata had analyzed several samples. “To be safe it must contain 0.5 mg / L of chlorine, but in the samples that we analyzed from various sectors of Challhuahuacho, the chlorine did not even reach 0.1 mg / L. With that amount it is impossible to eliminate the water’s bacteriological load. The municipality should do the cleaning and chlorination but they do not,” he said.

Figures from the Regional Health Directorate indicate that in 2017 chronic malnutrition had area increased by 30% over the 2016 figure. “Even medical personnel who have malnutrition and anemia. However, the most serious cases have been found in pregnant women,” he says. The biologist has previously worked in a health center in the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley (Vraem)—the epicenter of national cocaine production. He claims that health indicators in Challhuahuacho are more alarming. “There is more access to employment, but the quality of life is not better.”

Chalhuahuacho has 38 Quechua peasant communities and an estimated budget of 140 million soles this year.

The increase in malnutrition and anemia is related to changes in eating habits. As it has happened with other areas impacted by extractive activities, investment boosts the local economy. There is more employment and trade. “Children and adults now eat more carbohydrates and processed foods. The consumption of products from the area is being abandoned, “says Firata. Every day the health center receives on average of thirty children as patients.

As a remote rural facility, the health center does not offer all the specialties. In an emergency, patients have to travel to Tambobamba, located an hour away. More serious cases mean a trip to Cusco of eight hours by car.

The lack of ambulances means only patients with financial resources can receive attention in specialized hospitals. A doctor at the health center related the story of a child who immersed her hand in boiling water. “Although she needs specialized attention, she cannot travel to Cusco because his parents do not have money to pay for the transfer.”

The economic contrasts in this area are visible. There are two ways of understanding Chalhuahuacho: one is the lack of basic services in communities such as Chuicuni; the other is the full range of services that the mining company has granted Nueva Fuerabamba, the new site to which the community was transferred when the huge copper vein was discovered.

It is a huge residential complex consisting of five hundred identical houses. Each has three floors, a family garden and a fenced. The roads are paved. There is electricity, water, and permanent sanitation. The school has all the services and there is a fully equipped health center. Many of the comuneros who live here are traders. But for some the enthusiasm for moving was exhausted in the first year. “I can’t get used to it,” says a woman who sells candy at the school door. We are all together. There is no space, and sometimes we get stressed.”

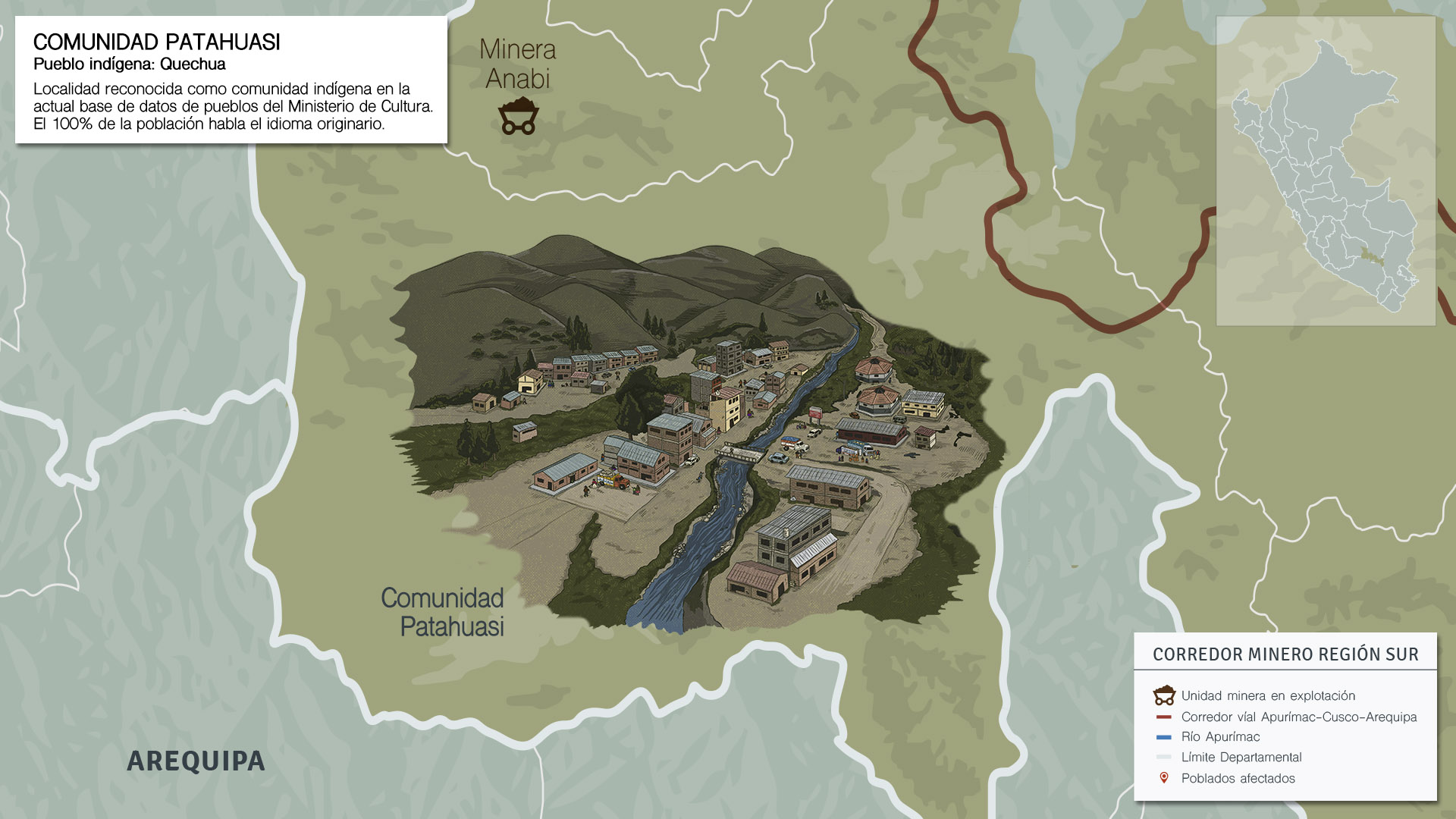

PATAHUASI

[The dispute between communities]

The Haquira district is four hours from Challhuahuacho. Three hours beyond, along a zigzagging road is Patahuasi. We met Ricardo Astuhuillca, Vice President of this Quechua community. His bucolic house on the border with the region of Cusco is surrounded by mountains. Sitting in his backyard his voice rises when he speaks of his fears about the installation of a processing plant by the Anabi SAC mining company at the headwaters of the river that supplies Patahuasi. “Nobody consulted us about it. We all depend on that river here.”

In May 2017, the Environmental Assessment and Inspection Agency (OEFA) ordered the company (which belongs to the Aruntani Group) to immediately halt the construction and operation activities of the Utunsa beneficiation plant. The authority found out that the company had installed work areas (wells, a cyanide destruction plant, and an electrical substation) in places other than those it had initially reported.

According to the environmental authority, these changes did not have an environmental impact assessment and therefore created the “potential risk of affecting the water quality of the Huayllani creek, which in turn could affect the health of the people and the environment.”

According to Ricardo Astuhuillca, the installation of the plant was only one of the problems that arose at the start of mine operations in 2016. The discussion about which communities were to be classed as falling within direct influence and therefore be eligible for compensation, generated a confrontation between members of the community and entire families. Rogers Ccoropuna, President of the community of Chuicuni, has defined this “social contamination among comuneros”.

The presidents of each community do not know each other, but they do understand the consequences of these clashes. Their capacity to negotiate with the company weakens. The members of the communities dispute compensation amounts and boundaries of their properties. A large part of the latter lack geo-referencing. Many property boundaries are not fully registered. The mining concessions have clearer boundaries than the indigenous territories.

In May 2017, the Environmental Assessment and Inspection Agency ordered the company to immediately halt the operation activities of the Utunsa beneficiation plant.

Astuhuillca believes that it was mining influence that encouraged a group of members of the community of Patahuasi to encourage the creation of Piscocalla, a town located next to Anabi SAC’s Utunsa project. “Piscocaya was created recently. Before, we were just one [community]. Now the mine has divided us. Before, we had working bees to repair the temple or the road. But now nobody wants to do it. Now we don’t even talk to each other.” He says that those disputes have also affected relationships between families.

The confrontations were also the consequence of the violation of a series of rights. More than half of the Quechua indigenous communities do not have their community land boundaries properly georeferenced. These lack titles and are not recorded by the Public Registry. It was under these circumstances that between 2012 and 2015 a large part of the mining projects in this area of the southern mining corridor were approved.

In this same context, publication of the database of indigenous communities with the right to prior consultation was discussed. The mechanism obliged the state to consult communities about projects or initiatives that might affect their lives, territories, and rights.

As a previous investigation by Ojo-Publico.com has revealed, it was during this period that the government of Ollanta Humala gained access to a preliminary database that identified Quechua indigenous communities in the southern mining corridor and decided not to publish it. The complete list only became known in 2016, when several mining investments were already underway.

Between Cotabambas and Antabamba, both in Apurímac, the Ministry of Culture’s Indigenous Peoples Database identified twenty-six indigenous communities. Patahuasi was one of them. It is also one of the oldest communities in the region, having been recognized in 1928. Until last year, however, the coordinates of the boundaries of its communal lands were not registered and had not been geo-referenced. Some 61% of its 500 families live in extreme poverty, and 99% speak Quechua.

There was never any prior consultation in Patahuasi and nor was there any in Chuicuni, even though the latter appeared in the preliminary database of indigenous peoples to which the government had access when it approved the commencement of operations at Las Bambas. Chuicuni did not appear on 2016 release of the final list of indigenous communities entitled to prior consultation, Rogers Ccoropuna is unaware of the community’s past or current status on the list.

Why did they appear previous but not now? Who is indigenous in Peru? The Andes is home to more than 70% of the entire indigenous peoples of the country. In the preliminary database that was filtered and later disseminated by Ojo-Publico.com in 2015 some 436 indigenous Quechua communities were registered in Apurímac. However, only 279 appear on the current list administered by the government.

The community of Chuicuni is recorded in the Public Registry, but its communal boundaries are not properly geo-referenced and registered. The community was recognized in 1986 and now has land that measures 854 hectares. The state’s argument for not to undertaking prior consultation in the indigenous communities near Las Bambas was that the database was not known and the geographical boundaries were unclear.

Rogers Ccoropuna explains that people in his community they have been unable to geo-reference their boundaries until now because preparing the technical reports requires a big budget. “We do not have the money to do all this.” What little money the community manages to raise has been used to build infrastructure such as the improvised network of pipes that carries the water from the spring to the heart of the town.

Communities located in the Las Bambas area of influence were not consulted about the modification of the Environmental Impact Study which eliminated the installation of an underground pipeline for the transfer of minerals (an ore pipeline) with a proposal to use a highway for the transport. “We were never made aware,” says Chuicuni's leader.

Until 2014, Las Bambas was owned by Glencore Xtrata, the Swiss mining giant. That year the company sold the project to a consortium of Chinese companies led by MMG Limited, a subsidiary of China Minmetals. At the beginning of the mining operations, the community of Chuicuni, like others in the area, was in favor of the mining project. “Many of us supported the project because we thought we were going to have a job. [Glencore Xtrata] offered us everything. Now when we complain they tell us that those deals were made by the previous owner. “

There was never a prior consultation in Patahuasi, nor in Chuicuni, despite the fact that both appeared in the preliminary databases of 2014

Javier Huillca, Vice President of the community of Chuicuni, says that when Glencore Xtrata owned Las Bambas the company committed to pay a sum for using its territory as for passage of the mineral pipeline. However, with the change of the Environmental Impact Study, and the replacement of the pipeline by the highway, Chuicuni was left without that compensation. For some time now, people have preferred not to buy trout at the Sunday fairs in Haquira and Patahuasi. “They are afraid it’s contaminated,” he says.

ESPINAR

[Loss of communal property]

Eight hours from Chalhuahuacho, a guzzling sound is emitted by the hoses that carry water to the house of Francisco Merma, in the Alto Huancané community, of Espinar, Cusco, at an elevation of almost 4000 meters. It is a violent noise, as if a monster was trapped inside. The hose should carry water pumped from a well. But there is no water. Thirty-seven years after the first mining operations in Espinar, an area in which high amounts of toxic metals have been reported, the Quechua communities located near the company lack access to safe water.

Alto Huarca was recognized as an indigenous community in 1928, and is also recognized as such in the current database of indigenous communities. Some 90% of its population speaks Quechua.

Not far from there, about 15 minutes by car, is the home of Olimpia Huillca, President of the Sol Naciente area, also located in Alto Huarca. To get here one has to cross controlled roads and land acquired by the mining company.

An investment project developed by the municipality of Espinar in 2017 installed pools and showers in several houses. But by the time the works were completed, the spring from which the waters was to be extracted had dried up. Olimpia now uses her shower to store rubbish.

We arrived at her house, as have two security people behind us in a van. They say nothing and wait fifty meters away from us. They did not identify themselves. “Pay no attention to them. They only do it to frighten. One of these days they will end up throwing us all out of here, “says Olimpia.

All the properties adjacent to Olimpia’s land were purchased by the mining company and her house is now an island. She has placed an electric fence that works with a small solar panel so that her livestock does not escape. Any attempt is met with a slight discharge.

Water tanks were installed in the Alta Huarca community, but the water never arrived. The people have been told that the spring has dried up.

Víctor Alvarez is one of the inhabitants of Alto Huarca and a guide to these labyrinthine roads that crisscross the mine areas and the fragmented communities is. He tells that in the midst of the promises of employment and benefits, the mining company helped the people prepare the technical file to geo-reference the borders of the community, and pledged to pay some expenses of the parceling of the communal lands by way of giving each comunero certain amount of money. Thus, each person would be owner of a property and not the community.

“In an assembly the community accepted the parceling and each one began to negotiate individually with the mine. That has weakened us.” Víctor Alvarez says it is more difficult to dialogue with the mine, because there is too much individualism. “Everyone is selling,” he says. It is for this reason that houses like that of Olimpia seem like islands with no way off.

The name of the notary office that carried out most of these kinds of procedures in Espinar is Gaona, and is owned by Oswaldo Gaona Chacón. We talked with him in his office about how the firm undertook these land sales processes between the community and the mining company. “It is not a purchase-sale with the communities, but a direct operation with the owners who have benefited from the allocation of land by the community. They are no longer comuneros,” says the notary.

According to his interpretation, “from the moment in which the community grants each one the property title, the individual ceases to be a comunero and becomes instead an independent private owner. The agreements are made directly with the mining company without intervention of the community.”

From the moment in which the community grants each one the property title, they cease to be a comunero.

- How many cases of buying and selling has your notary processed this 2018?

- The mining company

- ¿Cuántos casos de compra-venta ha atendido su notaria este 2018?

- So far this year I have had an average of thirty sales. The matter goes through a legal clearance process. They agree a price for the land and the form of payment, and once they have everything they bring me the agreement draft. My job is just to execute the agreement as a public deed. The law firm hired by the mining company sends me the agreement draft by fax and requests that it be registered as a public deed.

The Antapaccay Project extracts primarily copper and to a lesser extent silver and gold. In Espinar, Glencore currently holds 114 mining concessions with an area of 97,374 hectares. Of this total, operations in Antapaccay correspond to 7,944 hectares. In recent years, this area has been the scene of the biggest environmental conflicts due to the shortage of water and the high presence of metals in the environment.

In theory, there is a dialogue table with commitments undertaken by central government ministries such as mining, health, development, transport and the environment. However, the comuneros’ perception is that they have once again been forgotten. Espinar does not even have a permanent drinking water system. One of the most frequent complaints from communities in this area is the quality and exploitation of water for mining uses.

“I just want to live like they live,” says Don Francisco

According to Glencore’s sustainability reports, Minera Antapaccay captures around 15 million cubic meters of water each year from the Salado and Tagus rivers. Data provided by the Glencore Observer Network indicates that the company suddenly went from reusing 2.4 million cubic meters of water in 2013 to 55 million in 2015.

The company justified this enormous growth as due to the fact that it had water stored in the tailings dam, and had the capacity to recycle 78% of the water used by the mine and without discharging into water sources close to their operations. However, there is no way to verify these figures, because the ANA does not supervise the exploitation of the resource by the mining companies.

“There are several springs that are drying up,” says Víctor Alvarez. But there are no comprehensive studies or state entities that report or document these disappearances. From the house of Francisco Merma one can observe the progress of the mining project. A huge block has devoured what was once a hill. He says they are tired of demanding. “I just want to live like they live,” says DonFrancisco. He is referring to the water, because the mining camp in front of his house is never lacking for water.